-

-

- Access on: 2026-02-24 11:17:53 (New York)

Connect with us:

Connect with us:

December 22, 2024

Contributed by Sid Sung, Bitech Technologies Chief Innovation Officer

Today, North America boasts two prominent electric interconnection systems: Transmission Interconnection and Distributed Energy Resources (DER) interconnection. The Transmission Interconnection facilitates the large-scale transfer of electricity across vast distances, connecting generation facilities to the main grid. On the other hand, DER interconnection focuses on integrating smaller-scale renewable energy sources, such as solar panels and wind turbines, directly into local networks. In this evolving landscape, the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) is actively promoting interconnection advancements through the Innovation Interconnection e-Xchange (i2X), which is significantly enhancing the interconnection processes. The i2X initiative aims to streamline these procedures, making them not only simpler and faster but also more equitable for all stakeholders involved in deploying clean energy resources. Through these efforts, the DoE seeks to foster a robust infrastructure that supports the transition towards a sustainable energy future.

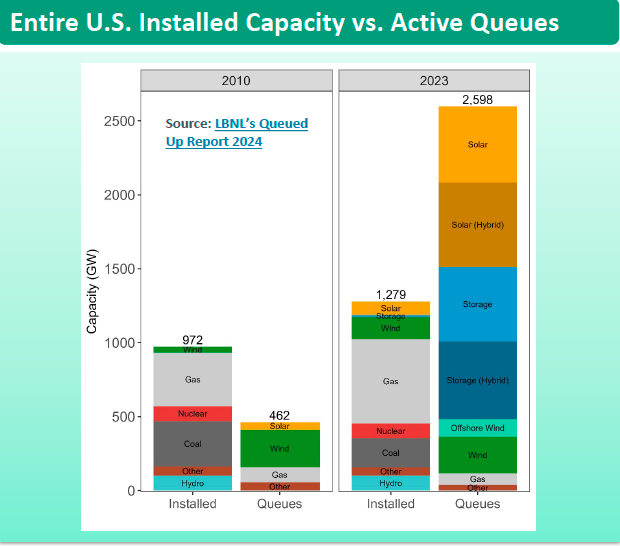

Between 2000 and 2010, the United States saw a steady volume of new transmission interconnection requests, averaging between 500 and 1,000 annually. This influx corresponded to an estimated proposed generation capacity ranging from 150 to 200 gigawatts (GW) per year. However, the landscape has transformed dramatically over the past decade. The number of new requests surged to between 2,500 and 3,000 each year, indicative of a burgeoning interest in expanding energy generation capabilities. This increase reflects a proposed capacity that fluctuates between approximately 400 to 750 GW annually. Such figures signify an astonishing threefold to fivefold expansion in both the quantity of interconnection requests and the associated proposed generation capacity compared to the earlier decade. This trend underscores a significant shift in energy production dynamics within the country, revealing an urgent need for enhanced infrastructure and strategic planning to integrate this expanding array of renewable and traditional energy resources effectively. The insights gathered from this data are further detailed in the diagram derived from the Lawrence Berkley National Lab (LBNL) Queued Up Report for 2024.

From the above diagram, we can see the completion rates are generally low; wait times are increasing. Only 20% of projects (14% of capacity) requesting interconnection from 2000-2018 reached commercial operations by the end of 2023. Completion rates are even lower for solar (14%) and battery (11%) projects. The average time projects spent in queues before being built has increased markedly. The typical project built in 2023 took nearly 5 years from the inter-connection request to commercial operations, compared to 3 years in 2015 and less than 2 years in 2008.

It is very obviously that Interconnection processes enhancements will need to evolve to handle this larger number of requests today and into the future, as policy and economic drivers continue to motivate significant resource development. The Need for Reform is critical to address rapid rise of interconnection requests and Expectation that these levels will remain in future due to load growth, plant retirements, and government policy.

In this blog, the Transmission Interconnection processes will be the focus, and we will talk about DER Interconnection in the future. However, there are many similarities for both interconnections will also outline in the future.

Interconnection is a crucial framework that outlines the specific rules and protocols new electricity generators, along with Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), must adhere to in order to connect seamlessly with the electric grid and ensure reliable energy delivery to consumers. This framework encompasses a diverse array of generation technologies, including but not limited to wind, solar, natural gas, energy storage solutions, nuclear power, and other emerging resources. The term "interconnection" also encompasses the technical prerequisites and legal processes that facilitate the interface between a generator and the electric grid. Depending on their capacity and type, generators can establish connections either with the transmission grid or the distribution grid; each pathway presents distinct interconnection procedures governed by separate regulatory entities. These procedures are designed to maintain system reliability, enhance operational safety, and protect both consumers and utilities in an increasingly complex energy landscape.

Every regional grid has its own set of rules, but most require every project to undergo a rigorous, multi-step study process to assess potential impacts to the grid from the new generation. These studies often result in requiring the generator to fund any necessary upgrades to grid infrastructure before securing an interconnection agreement. Any grid upgrades identified during the study process must then be completed prior to the generator coming online.

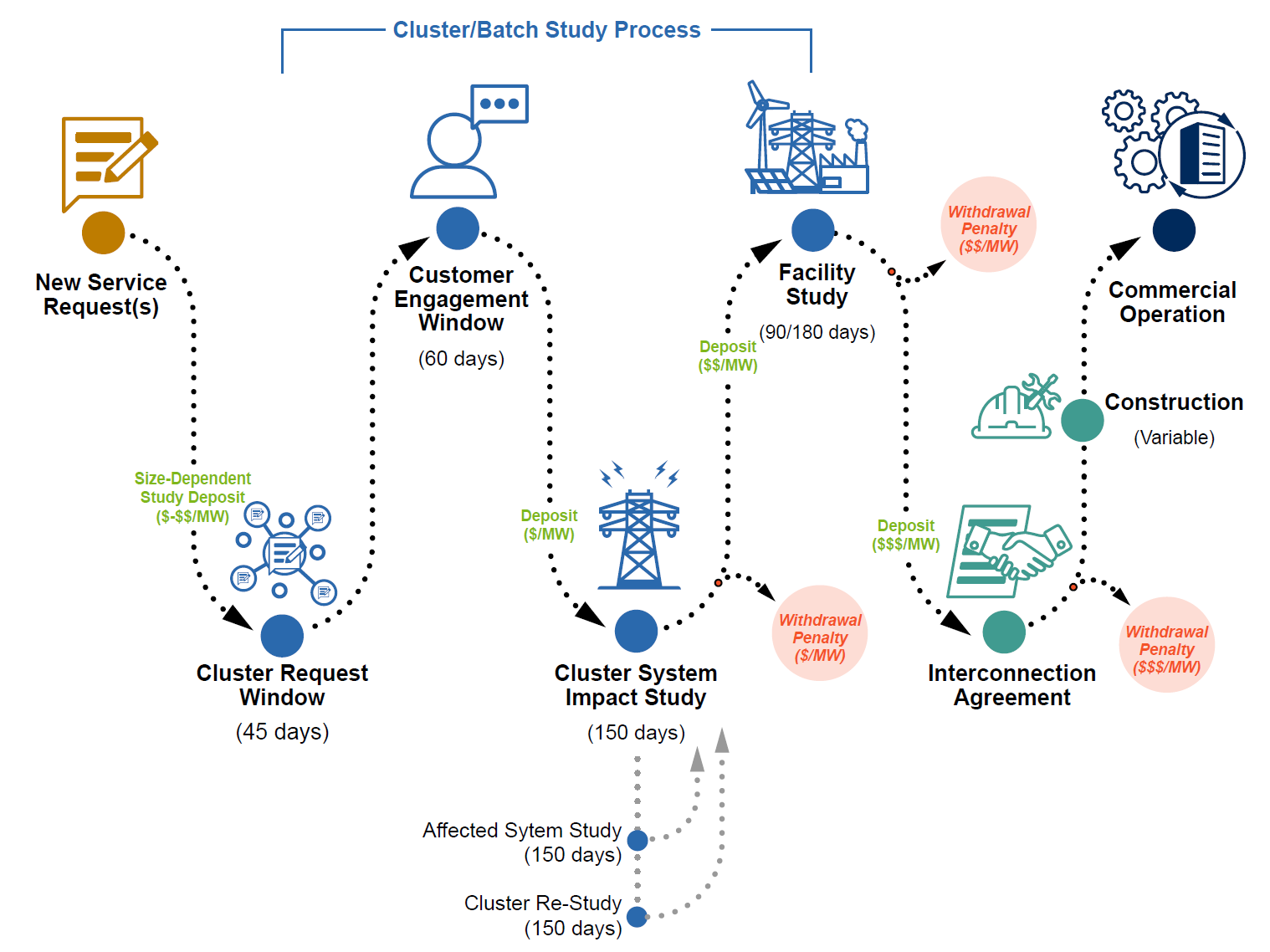

For transmission interconnection this process is handle by ISOs/RTOs or Grid Operators. The transmission interconnection process is different by region but in general this process is “entering the queue”. The following outline the step by step for the transmission interconnection process.

A project developer initiates a new interconnection request (IR) application and thereby enters the queue.

Project developer places a deposit.

Project developer eventually demonstrate it is likely to secure land-use agreement for the project location (also called “Site control”).

Series of small studies are conducted additionally.

Once the transmission Interconnection application and deposit have been submitted, the ISOs, RTOs or grid operators will work with the project owner (“interconnection customer”) on a series of study assessing the projects potential impact on the grid. It is also establishing what new transmission equipment or upgrades may be needed and assigns the costs of that equipment.

The three typical studies are outline in the following:

Feasibility Study: determines whether plugging the project into the grid would cause electrical problems and assesses whether transmission upgrades are needed to prevent problems.

System Impact Study: requires more detailed information from the customer and assesses grid impacts in more detail. The project’s design can still change at this stage.

Facilities Study: estimates in greater detail the costs of equipment, engineering, and construction of the facilities needed (such as wires and substation upgrades) to connect the project to the grid. At this point, the design of the project is fairly certain.

After each study is complete, an interconnection customer makes the determination to advance to the next phase, based on the information provided by the ISOs/RTOs and grid operator.

Studies may need to be re-done if a proposed generator higher up in the queue decides to cancel their project and drop out of the queue, as it could change the impact and upgrade needs for other proposed generators. When this occurs, it can add to the review time for a project.

In some cases, interconnecting new projects causes impacts beyond the local transmission system, into adjacent transmission systems.

When there could be effects on other utilities’ or grid operators’ systems, they will perform “affected system” studies, which evaluate similar information to the three studies mentioned above.

“Affected System” Study: Affected system studies can take longer to be finalized in many regions. Better coordination between adjacent transmission systems can help to determine costs and prevent significant issues.

After the studies are complete, an interconnection customer will determine whether the upgrade costs mean the project can economically interconnect to the grid.

Interconnection Agreement (IA): If the project is determined to interconnect to the grid, the interconnection customer and the ISOs/RTOs or grid operator will sign a IA. A contract between the ISOs/RTOs and the generation owner that stipulates operational terms and cost responsibilities, the plan for building the facilities and implementing the upgrades that will allow the project to connect to the electric grid. A project cannot interconnect until those improvements are constructed.

The following diagram summarized the above processes based on LBNL study:

In April 2024, a significant shift was on the horizon for the energy sector as the Department of Energy (DoE) unveiled the "Transmission Interconnection Roadmap – Transforming Bulk Transmission Interconnection by 2035." This roadmap represented a strategic framework aimed at revolutionizing how electricity transmission interconnections are managed and optimized in response to an ever-growing demand for power.

The ongoing evolution of our society's energy needs had put immense pressure on existing systems. Conventional demand from residential and commercial sectors was surging, fueled by population growth and rising living standards. At the same time, the rapid proliferation of AI data centers demanded exorbitant amounts of energy, which only compounded challenges already posed by extreme weather events resulting from climate change. These multifaceted pressures highlighted essential deficiencies in current transmission interconnection processes.

Recognizing this dire need for transformation, the DoE meticulously organized both nearer- and longer-term solutions that would cater to a diverse audience comprising utilities, regulatory agencies, and technology providers—all integral players within the transmission ecosystem. Stakeholders were invited to engage deeply with these proposed solutions to foster collaboration that could lead to sustainable practices in meeting future electricity demands.

The roadmap outlined a clear vision: create an efficient interconnection process that minimizes operational barriers while maximizing reliability and efficiency across all sectors involved. It emphasized advanced technological integration that would streamline procedures for connecting new generating resources—ranging from wind farms in remote areas to rooftop solar panels spreading across urban landscapes. Moreover, it called for enhanced collaboration between local governments and utility companies, ensuring that new infrastructure can be built swiftly without unnecessary delays or bureaucratic red tape.

In workshops held across various regions over the following months, experts convened to discuss implementation strategies rooted in feedback from communities directly affected by these changes. Harnessing innovations like smart grid technology, automated system monitoring, and predictive analytics became crucial focal points then even more so than before as stakeholders began aligning their resources with shared goals illuminated through partnership discussions.

The transformational journey envisioned through this roadmap would ultimately require commitment not just from industry leaders but also involvement at grassroots levels as all segments of society started recognizing their roles within an interconnected electrical framework capable of adapting seamlessly amid growing demands driven by modernity’s technological advancements.

As we approached 2035 with hope—and urgency—the Transmission Interconnection Roadmap cast its light upon pathways toward efficiency that could not only mitigate strain on existing infrastructures but also elevate our collective ability to harness energy sustainably for generations ahead.